I began my residency at Treadwell’s with the intention of submerging myself fully in all that this beautiful shop and centre has to offer. My first taste of this was through an evening workshop titled “Meeting the Gods of Resurrection”, delivered by the wonderful Rebecca Beattie. At the tail end of this workshop was a guided meditation, where we were invited to visualise ourselves in a safe and familiar place, and then to see if any indication of a deity presents itself. I decided that whatever/whomever presents during this meditation would be the symbolic and archetypical guide for the development of my creative practice for the three months that I am here.

I have always been a good visualiser, and (perhaps unsurprisingly for a poet) do not struggle with deriving symbolic meaning from the everyday, the imagined, or the dreamed. Quite quickly, I visualised the face of a goat, hosting a curious, though warm, smile. Though my knowledge of classic mythology is scant, I recognised this individual as Pan. This was an unsurprising manifestation; the location that I had visualised myself walking to during the meditation is one that my dog and I visit regularly on our walks. It is a quiet place, with a good view of the valley, and a good selection of sticks. We sit here together almost daily; I bird-spot, the dog chews. My dog is called Panda; increasingly we call her Pan. She is a hybrid – part wolf, part dog; part domestic, part wild. She is the being that drives everything that I do, and ours is potentially the most significant relationship I have formed.

Allowing this figure of Pan, these Pan values, to influence and guide my writing, largely feels like a recognition of what is already there. In particular, I am intrigued by this idea of hybridity. Much of my writing explores notions of monstrosity, of half-humanity. Often this is tied to trauma, or conflict. As a woman, I think this makes some sense. The domestic vs the wild is not an uncommon feminist or womanist investigation. Many of us grapple with this notion of domestication as something that can feel like a falsehood imposed on a more authentic version of ourselves. Though all human beings are expected to engage with proprietry, there is an argument for the unequal and gendered distribution of such expectations. In terms of conventional (patriarchal and colonial) beauty standards, “the ugly” is often the uncultivated body – unshaved, bare-faced, bra-free, unfiltered. Incidently, Pan, in the shape of half-goat half-man, is often depicted as ugly and undesirable.

In a very simplistic sense, we are all hybrids – combinations of the animal us (dictated by bodily mechanisms and demands that it is impolite to discuss, recognisable in the internal rages that we smile through, the barely-there impulses to run out of the office and jump into the ocean…) and the human us we present to our communities (reasonable, restrained, clean, polite, considered). Using other forms of language and knowledges, some might refer to these aspects as the id and the super id.

Much of my previous poetry has explored such themes, using human/non-human hybrid imagery in relation to the movement from childhood to womanhood. I feel I am far from alone in having experienced womanhood (particularly that grown into during the early naughties) to be a deeply restrictive role. Having spent a portion of my childhood semi-feral in rural Devon, metres from the South West Coast Path, this transition felt particularly violent.

So I feel in good company with the figure of Pan as a creative mascot. Like Pan, I enjoy the finer, distinctly human, things in life; good wine, beautiful music, and of course books and poetry. Pan(da) also enjoys much that domesticity has to offer: regular meals, a warm comfortable bed. But, like Pan, we are both also ruled by things altogether more wild. My family will tell you that my tendency towards the impish is bordering on problematic. I can be distasteful, disrespectful, unruly, and hard to manage. Pan(da) likes to roll in the filthiest things she can find – I’m confident she does this to prove a point. She is not biddable like a domestic dog. Sometimes it is clear that she knows what is being asked of her, but she is simply unwilling to do it. She will often take her stance while staring you straight in the eye, with a canine smile across her face. I believe she also enjoys the impish impulse a little too much.

In my understanding as a creative practitioner, this balancing of the domestic and the wild speaks to the poetic experience. When writing poetry we are often in the process of seeking the rawness that characterises truth, the messiness of the moment, the gritty and the granular that gives experience its taste. But we are also (at least if we hope to write something “good”, whatever that means) aiming to balance this alongside something entirely more domestic: refinement, clarity, discipline, craft. I understand that even those who have no intention of developing a professional career out of writing or poetry can find themselves overwhelmed by the blank page, and their creativity blocked by an internal narrator that criticises their writing as “not good” before it has even had the chance to fully form. It is this issue that I hope to address in my Treadwell’s workshops, titled “Rewilding the Self Through Poetry”.

Armed with these half-formed (pun intended) musings on hybridity and wild expression I arrived at the shop for my first day. As I was shown around the space, my guide pulled back some curtains to indicate where I might be able to access an outside area if I needed a moment to myself. Leaning against the window to this area was a large plasterwork depicting Pan, teaching a child to play his pipes. It was all the confirmation I needed that I am in the right place, heading in the right direction, with exactly the right intentions.

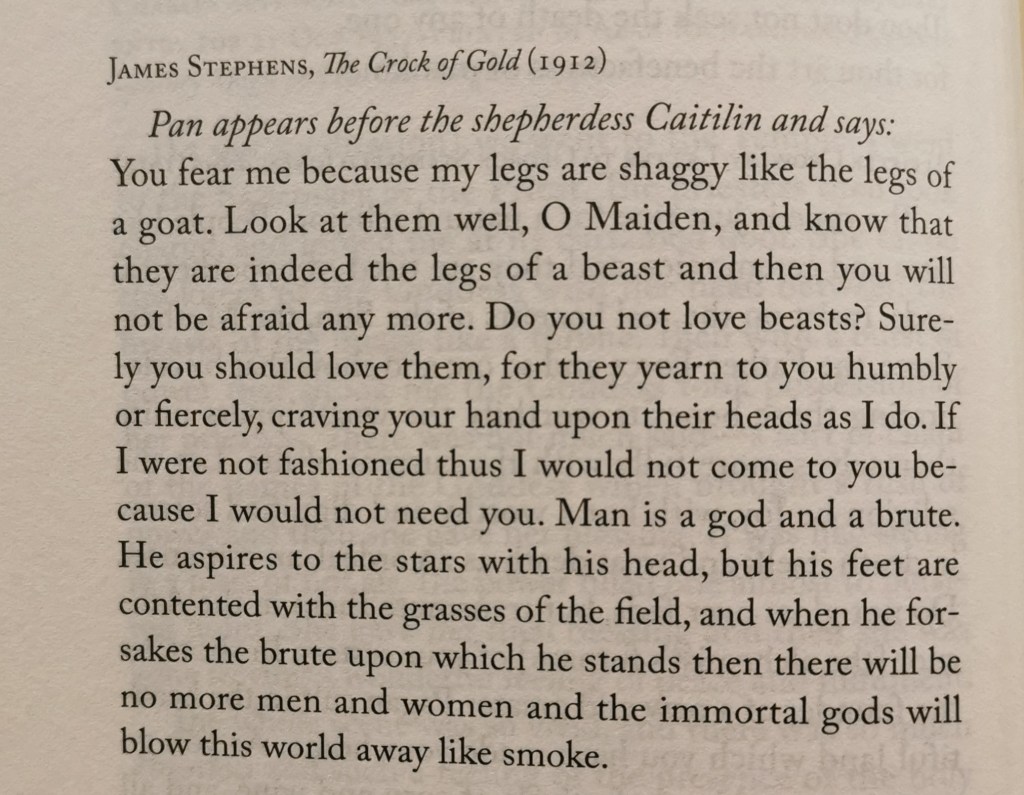

While Pan is often associated with overtly masculine energy, I think there is a lot in his symbolism and meaning that holds deep liberatory resonance for women. Christina (Treadwell’s owner) shared a beautiful poem with me, which further compounded my certainty on this. I have shared this poem in turn, in the form of a photograph which is an excerpt from Christina’s wonderful book ‘Dreams of Witches’, pictured below.

Poetry, more than any other art, has the capacity to straddle liminality and to speak in wild-tongues. I am so excited to see what comes from this residency, as I embrace my beastliness.